Nighthawks and nightjars of the family Caprimulgidae were once erroneously referred to as “goatsuckers” because they flew into barns at night to suckle on goats. Inappropriately named, nighthawks are not as nocturnal as once thought, nor are they related to hawks. They are active at dawn and dusk usually seen swooping and twisting high over fields, rivers, and towns in search of insects.

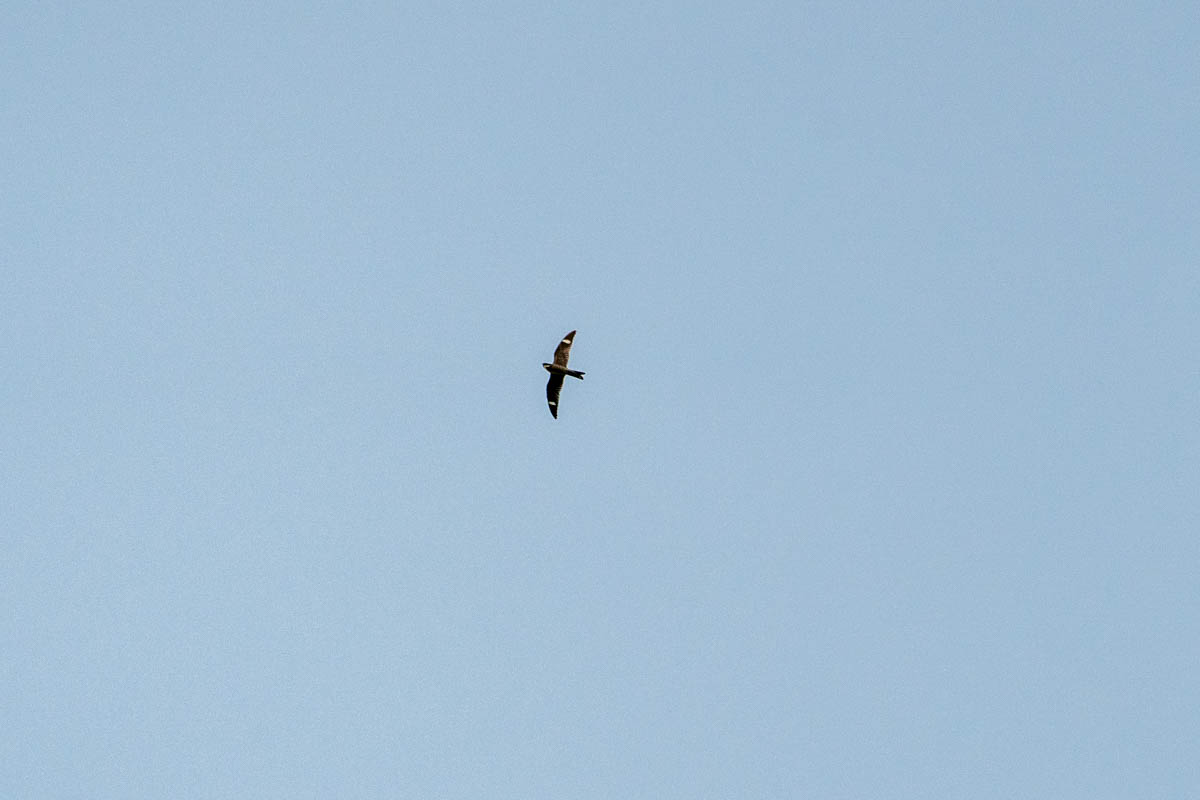

During the day, they roost on the ground or perch lengthwise on a branch. Cryptic colors aid them in blending in with their surroundings. In flight, they are easily identified by their erratic “bat-like” pattern. A white wing bar and white chin are other distinguishing features. Usually solitary, they form large, loose groups when feeding or migrating.

The birds begin their southward journey in late August and early September to South America where they will spend the winter in the Amazon rainforest and tropical savannas of Brazil. During fall migration, birds travel southeast through Florida, cross the Gulf of Mexico, stop in Cuba, and enter South America through either Ecuador, Colombia, or Venezuela, and then east to Brazil. This fall pattern sends them over the Blue Ridge where we can see large numbers this time of year. Come spring, they migrate back to their nesting grounds to nearly the exact location of the previous year. They return northwest through Brazil, across the Gulf of Mexico, stopping in Cuba, continuing northwest through the United States. This loop style migration keeps us from seeing them on their return flight.

Limited breeding bird survey data suggests a substantial decline in numbers of this species. It has been listed as threatened in Canada -- a decline of about 50% has been noted there over the past 3 generations. The 2014 State of the Birds Report lists common nighthawk as a “common bird in steep decline”. Across North America, threats include reduction in mosquitoes and other aerial insects due to pesticides, and habitat loss including open woods in rural areas and flat gravel rooftops in urban ones. Nighthawks are also vulnerable to being hit by cars as they forage over roads or roost on roadways at night. Creating nesting habitat by placing gravel pads in the corners of rubberized roofs and by burning and clearing patches of forest to create open nesting sites has been shown to have some success.

So, from the last week of August through the first week of September, enjoy the lovely pre-fall evenings outside looking up. How many common nighthawks do you see?

Photo credit: Steven Hopp

Cited Sources:

Brigham, R. M., J. Ng, R. G. Poulin, and S. D. Grindal (2011). Common Nighthawk (Chordeiles minor), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.213

Cornell University. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Common_Nighthawk/lifehistory

Canadian Journal of Zoology. https://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/10.1139/cjz-2017-0098#.XXFui5NKjK0